Each year, NSWA helps judge various portions of the Caring for our Watersheds competition which is hosted by the Battle River Watershed Alliance. The competition invites students from across the province to come up with innovative and creative solutions to watershed issues. This year’s winner created a unique board game that encourages participants to reconsider and re-think their relationship with water.

About Caring for our Watersheds

The Caring for our Watersheds (Alberta) was launched by the Battle River Watershed Alliance in 2007. Students in grades 7-12 from across the province are invited to identify a watershed problem and present one realistic solution. Proposals are submitted online and must answer a variety of questions around how the project will help, who it is aimed at, what supports would be needed to implement the project, a budget, visuals and a connection to the UN’s 17 Sustainable Development Goals.

From the 200+ entries, ten finalists are then given time and money to implement their solutions. The finalists gather at the Reynolds Museum in May to present their projects to a panel of judges, which includes one of our NSWA staff. All ten finalists win prize money, with the winning recipient(s) receiving $1000 as a team or individual – as well as $1000 for their school.

This Year’s Winner: Honouring Métis Teachings and Protecting the Land

This year’s winner is Dutch Bruce, who attends Bishop Lloyd Middle School in Lloydminster. Dutch is part of the Land-Based Cultural Leadership Program taught by Derek Hyland. The intensive yearlong program for Grade 8 allows students who value outdoor learning to grow in their leadership and cooperative skills through hands-on, project-based learning. Students prepare for the future through collaboration and respectful interaction with Indigenous culture, Elders, and knowledge keepers. Bishop Lloyd school has won top spot at Caring for Watersheds four times, including Dutch’s older sister, Sadey, who won last year.

For his project, Dutch created a board game called River Rescue. He wrote in his proposal, “As a Métis person, I feel a strong responsibility to protect the land and water. The game uses Indigenous perspectives, such as thinking seven generations ahead when making environmental decisions. By creating River Rescue, I hope to teach students the importance of water stewardship.”

Dutch drew wisdom and inspiration from local elders and the 12 Red River Cart Teachings/Métis Values. When asked about which of these values stood out most to him, Dutch said that respect and love are important for him because they are part of how we see friends and family as well as how we should feel and act in relationship to water. He was inspired to create a board game because he says he “didn’t want to do something boring” and wanted to create something that required active participation.

The Elements of the Game

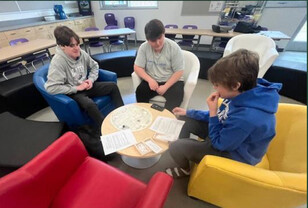

The Game contains several challenges and elements that the players must navigate. When asked what he enjoyed most about the project, Dutch says, “I put a lot into the cards.” The cards draw the players into different aspects of caring for water in ways that are informative, thought-provoking and fun.

Challenge Cards introduce players to real-world environmental issues, encouraging them to make decisions that safeguard the watershed. Wisdom Cards provide insights from Elders, Knowledge Keepers, and environmental specialists, blending cultural teachings with scientific understanding. Players earn Rescue/Protection points by taking environmentally responsible actions that benefit the river and its surrounding ecosystem.

The 12 Red River Cart teachings are integrated throughout the game, guiding players as they consider activities such as tree planting, proper litter disposal, and understanding the importance of beavers on the landscape. Coyote Crossings also introduce a bit of playful mischief into the game as the “trickster” character causes players to gain or lose tokens, move backward or forward or skip a turn. The game closes with a sharing circle where players each get to share what they learned from the game and express their gratitude for its teachings.

Teamwork, Input and R&D

Dutch mentions various people who were part of his support crew for the project. These included Knowledge Keepers Clint and Sandy Chocan who shared Indigenous teachings and wisdom about water protection, Elder Vivian Whitstone who provided traditional knowledge and guidance to deepen understanding for he and his fellow grade eight students. Dutch also got some insights about the natural world from president of the Lloydminster & District Fish & Game Association, Dwayne Davison. Dutch’s Mom and sister helped him design and paint the visuals for the game and once he’d started building the game, Dutch also recruited friends to help trial the game.

His teacher Derek also provided feedback and resources to Dutch throughout the whole process. Derek says, “There's a whole culture of hard-core board gamers and Dutch met with a couple of them at a board game store across the street. He met with some people to get feedback on the game and he took them various versions of it to play. They observed him and his friends playing it and then gave him notes on how to improve the game. So, there's some cool iterations of how it got created.”

Target audience: Who is it for?

Dutch and Derek say they hope the game could be used by schools such as the other grade 8 classes in Lloydminster. Further away, Dutch said it could be adapted for other rivers and watersheds in Alberta. He also proposed selling it at Farmer’s Markets or for be sold at local businesses or to nature clubs and organizations.

Other projects and future aspirations

Derek says that one of the other finalists from his class was called Life Stream and students Evan and Hudson had been planning to plant willow to deal with cyanobacteria in a nearby provincial park.” He adds, “They're still trying to lock that down. They're kind of stuck in getting permissions to plant right now, but they're trying to find outside agencies to help them.”

Dutch is hoping to get his game reproduced but there are logistics around printing so that each game doesn’t have to be hand painted.

Derek finished by saying that in an age where there are differences and tensions about causes, these projects reflect a hopeful way of dealing with complex issues. He believes that by learning about sustainability and gleaning from traditional teachings and working with elders these students are learning “how to be good caretakers of the land and reciprocal in our relationship – not just taking from it”.

Learn More

Find out how to get involved with Caring for Our Watersheds

Check out the NSWA's Youth Water Council where you'll team up with other high school students in our watershed to come up with an innovative project to address watershed issues.